The demand to solve increasingly complex problems is accelerating beyond the capabilities of traditional computing approaches. Quantum computing promises to revolutionize a host of industries by enabling rapid solutions to complex problems that are currently intractable for more traditional – or classical – computers.

As a primary funder of quantum research since 2009, IARPA-sponsored efforts have resulted in multiple world-record demonstrations of quantum computing capabilities, including achieving a “Quantum Advantage” – when a quantum computer can solve a problem more efficiently than a classical one. IARPA-funded quantum efforts have also led to over a thousand publications, dozens of patents, and the 2012 Nobel Prize in Physics.

In part one of this two-part episode, we sit down with former IARPA Program Manager, and resident quantum expert, Dr. Michael Di Rosa to talk about his journey to IARPA, what quantum computing is exactly, how it differs from more traditional computing, and much more.

| Timestamp | Caption |

|---|---|

|

Intro: IARPA sponsors research that tackles the intelligence community's most difficult challenges and pushes the boundaries of science. We start with ideas that often seem impossible and work to transform them from a state of disbelief to a state of just enough healthy skepticism or doubt that by bringing together the best and brightest minds, we can redefine what's possible. This podcast will explore the history and accomplishments of IARPA through the lens of some of its most impactful programs and the thought leaders behind them. This is IARPA, Disbelief to Doubt. Welcome back to IARPA, Disbelief to Doubt. Dimitrios Donavos: Welcome back to IARPA Disbelief to Doubt. I’m your host, Dimitrios Donavos. In this episode, we explore the frontiers of physics by taking a journey through the quantum domain where a particle can be in two places at once and the rules of our everyday world don’t always apply. Quantum computing promises to revolutionize a host of industries by enabling rapid solutions to complex problems that are currently intractable for more traditional – or classical – computers. As a primary funder of quantum research since 2009. IARPA sponsored efforts have resulted in multiple world-record demonstrations of quantum computing capabilities, including achieving a “Quantum Advantage” – when a quantum computer can solve a problem more efficiently than a classical one. IARPA funded quantum efforts have also led to over a thousand publications, dozens of patents, and the 2012 Nobel Prize in Physics. In part one of this two-part episode, we sit down with former IARPA Program Manager, and resident Quantum expert, Dr. Michael DiRosa to talk about his journey to IARPA, what quantum computing is exactly, how it differs from more traditional computing, and much more. Take a listen. Dimitrios Donavos: Dr. Michael Di Rosa, welcome and thank you for joining us today on IARPA Disbelief to Doubt. Michael Di Rosa: Thank you, Dimitrios. It's a pleasure. Dimitrios Donavos: Michael, you have mechanical engineering degrees from Drexel, Penn State, and Stanford, and you arrived at IARPA via Los Alamos National Laboratory, where you were on assignment managing the Trapped Ion Quantum Computing Portfolio for the Laboratory for Physical Sciences, or LPS. Take us back to the beginning and walk us through what sparked your desire to pursue a career in mechanical engineering and how you ultimately ended up working on trapped ion quantum computing. Michael Di Rosa: Perhaps like many from a young age, I was always interested in how things work. And so, I would take things apart, put them back together, usually all the pieces, and learn kind of experiential, you know, that way. And know, always kind of a mechanic about the house and also for some employment in my high school days, things like that, junior high. And so that kind of gave me the entry into mechanical engineering. It is...Gosh, as things went on, as you went over that arc going through from Drexel to Penn State to Stanford, increasingly, and always in the back of my mind, I was always interested in not only how things work, but why do they work? Why is this possible? And so, I think within that kind of came the transition to engineering and science, I think as perhaps I had always been, just one foot in each, the science from theory to math getting my hands dirty and trying to put it into practice. So, I've always tried to seek both, I suppose, you the practical side, but also kind of the far-reaching blue sky and what if that can be pulled in and put into practice. Dimitrios Donavos: So, in discussing that arc, what ultimately led you to IARPA? Michael Di Rosa: So, at Los Alamos, I was presented with the opportunity to join the Laboratory for Physical Sciences in their quantum computing group as a program manager running the Trapped Eye and Quantum Computing portfolio. And that was an interdisciplinary mix that I really enjoyed. Although as a program manager, it was an opportunity to set objectives in quantum computing for these particular physical systems. And that incorporated some of the engineering and physics I knew about for determined ends in quantum computing, at least for these physical systems. I returned to Los Alamos and then came the opportunity about a year and a half or two later to join IARPA as a program manager. And that was in truly IARPA fashion for a program. That was an opportunity to set an objective for the community in quantum computing. I undertook a program that was ongoing in quantum computing and as that was nearing its conclusion had an opportunity to extend that further into the next major leap. But that really was a grand opportunity to set a destination for the community as a whole and define what that journey was going to be so it's more meaningful both to the community, to IARPA's missions and also have it meaningful as part of a national imperative for quantum computing. So that was a fantastic outlet. Dimitrios Donavos: Along the way, who were some of your most influential people in your life, including your mentors, and how did they impact you professionally, personally? Michael Di Rosa: Well, I guess over life, guess maybe I can count myself lucky as having perhaps too many to enumerate. And certainly, there were many through the educational sphere, through team sports and things like that. And they continued on into education and into my professional career. And I think there were those that certainly had every bit the enthusiasm and passion for their topic as they did the ability to treat it with humor and also humanity. And I think it's those that I recall most fondly and try to carry with me wherever I go. Dimitrios Donavos: Where do you remember your first experience with quantum? And what about that motivated you to want to pursue that as a scientific topic of interest? Michael Di Rosa: Again, it came kind of in that application of quantum mechanics and my graduate work increasingly began to draw on a field of laser spectroscopy, spectroscopy in general. And so that's often the science of learning about your environment through medium's response either to laser light or how the medium transmits that information in particular wavelengths of light. So, you can learn about what's there, what are the conditions, what reactions are going on and things like that. So to be able to combine or actually to learn about a medium through spectroscopy, you also need to know the basics of spectroscopy, sort of apply theory so that when you make a measurement, you can interpret that measurement into something that's meaningful. The temperature of a medium, the speed of a gas, the constituents that are in a reaction So increasingly I became really interested in learning as much as I could on both sides of that, the theory of spectroscopy and then also its applications. Dimitrios Donavos: What excites you the most about being a program manager at IARPA? Michael Di Rosa: I had spent time, let's say on the other side of the equation, the one actually writing proposals and doing the research. And with IARPA certainly came the opportunity to give back to that community, but in a different way, to create the opportunities that I had benefited from, both as a student and also in my professional career. And the other difference is that through being a program manager you get to give the field a nudge and a push in a particular direction. And more than that, you get to set a stage on which and give yourself a front row seat and also arrange what acts and how it's going to take place. And it's just also becomes a fascinating way also to learn through others. Certainly, in research you live vicariously, but it's a grand opportunity to set that opportunity for the field to go forward, to sort of unleash their creativity. So you're able to, with starting a program, being able to unleash all the resources and creative ideas and very good people in that particular field that you couldn't do by yourself, certainly. Dimitrios Donavos: I think to that point, one of the advantages of being at IARPA is that the organization really brings together these communities across academia, government, industry, small business, in unprecedented ways to tackle these incredibly ambitious problems. And oftentimes, it's harnessing this technological talent across the globe towards solving a problem that has a significance for both the intelligence community and for the scientific community. What has working within those communities meant to you personally? And how do you see that effort continuing even after you leave IARPA and your tenure at the organization comes to a close? Michael Di Rosa: It is important to, I mean, as you said, to harness really the best ideas internationally. If there's a particularly pressing problem and the science being democratized, it's good to tap into different approaches and not be so parochial about it. And one way to sort of enliven that range of approaches is to reach out internationally. So that's been really rewarding. As program manager, you can have the opportunity to take site visits to where the research is being done in this country and abroad and so that itself is quite educational. The different approaches that the different teams have, also the different way organizations run, that's all been really edifying for me, certainly. For the program itself, how that goes on and things at IARPA, I'd say that, you know, IARPA through the way it forms programs gives it structure for this type of model, you know, to continue to again, to reach out to, you know, solid groups, the best ideas wherever they might be to solve some of these problems. So, I'm confident of course that that would continue. Dimitrios Donavos: When we look at the larger portfolio of research at IARPA, it's clear that the quantum programs have really resulted in the most robust publication history. And we've had significant achievements that have happened on the programs and high impact publications. For those folks that are listening, it's important to emphasize that when you work with IARPA, you maintain the ability to publish and that you have IP rights for your technology. How critical do you think that is in terms of the way performers are energized in terms of tackling such a difficult problem when they know that the fruits of their labor will actually be meaningful to the scientific community broadly? Michael Di Rosa: Absolutely. On our programs, and I would think across IARPA, they should know that the work that they are doing, every bit of it could be put toward their own professional advancement. know, whatever inspires them in that way, whether it's publications, whether it's patents, even forming a startup company. All of that is their property. Every professional outlet is certainly available to them in the work they do for IARPA's programs. Dimitrios Donavos: So, we talked a little bit here about accepting risk of failure. One of the things that we try and do at IARPA is when we do have technical failure, we try and learn from it and incorporate that into the next effort. I'm curious in your own career, what would you describe as one of your biggest failures and what did you learn about yourself from that experience? Michael Di Rosa: I pause mostly because not that I haven't had failures. Certainly, there have been attempts to do particular things and they didn't quite pan out, whether in the laboratory, other things, but for me, that's always been a great learning opportunity. And figuring out, had, you perhaps, you embark on something and there's assumptions about why it ought to work and then it doesn't. And so, for me, that's often a path of inquiry into why it didn't work. And so, I don't see those failures that saves disappointments and perhaps that's not why, perhaps that's why they don't stick with me you know, indelibly, but there were always opportunities to learn. It's just part of the learning process. Dimitrios Donavos: Well, when you're working with such a high-risk research, I think you have to be willing to accept that risk of failure and understand that you'll be learning from it and that learning will eventually inform an effort that hopefully will have some success as a consequence of that. I want to get into a little bit more on the theme of today's episode. And I want to start with very basic question. What exactly is quantum computing and how does it differ from conventional computing for our listeners who may not really fully appreciate the difference? Michael Di Rosa: Sure. So, for quantum computing as a mode of computing, it is radically different than how we proceed with the Boolean algebra of classical computing. And let me just give an example, entirely theoretical, hypothetical at the moment. You know, one particular algorithm, you know, for quantum computing that is well known is for factoring large integers, factoring semi-primes. And it's the basis on which public cryptography is based. So let's take for granted some of the estimates that theorists are telling us under varying assumptions that to do this with a quantum computer would take, I'm going to introduce qubits, but would take about some tens of millions of qubits. And the algorithm itself would take some tens of billions of steps. And after that, through this algorithm with a quantum computer, you would arrive at an answer to that particular problem. That if left to a classical computer would take, I don't know, by round estimate, a quadrillion years to solve. Yes! Dimitrios Donavos: That's a long time. Michael Di Rosa: That's a long time! You know, longer than the age of the universe. So that's what this is just in theory, what a quantum computer can do. But let me just give you an example of what that means for efficiency or exponential efficiency. So, we use two numbers. It was tens of millions of qubits. That sounds like a big number, but on our processors and our computer, you know, like a CPU, a central processing unit, has some billions of transistors, kind of the classical cousin of qubits. So, okay, you know, big numbers, but we're familiar with those types of big numbers. Well, it took tens of billions of steps. Well, we're actually familiar with those because those same processors on our laptops and such, they operated gigahertz rates. It's a, you know, a billion instructions a second. So, this particular algorithm under those kinds of numbers that would solve what is a classically intractable problem into just seconds within a minute or so. Now there is no machine even remotely like that. It could certainly take, you know, decades, you know, to achieve. So again, this is all on paper, but there is the allure then for quantum computing to be applied to other problems and perhaps on machines, you know, far less in scale to probably the earliest visionary ideas for using quantum computers. And that was for simulating physical systems, for simulating physics and related problems in chemistry, biology, medicine, say ranging from making inquiries into how could we arrive at superconductivity at room temperature? How could we discover drugs and cures faster than we do now? And perhaps some of those outlets bear fruit in the shorter term. So, there's this sense that quantum computing, well, I think it is not superior in every regard to classical computing, but there are some classes of problems where it might excel like that. And so that gives it impetus to discover what this frontier of computing might be like. Dimitrios Donavos: So, the differences between quantum and classical computing are significant, but there's also this necessary symbiosis where you actually need both. Can you just describe to our audience what we mean by that? Michael Di Rosa: A quantum computer, well, people tend to think of, there's quantum computing and it's going to be much like my laptop, or it's going to be like some supercomputer and it takes care of itself. But actually, as conceived presently, a quantum computer is going to take a lot of care and feeding from the classical world. The qubits themselves, they need control from the outside world. They need to be told what to do. So there's signals sending in controls for gates and such, all the logical operations that make the computation go. Qubits need to be measured. Often, depending on the type of algorithm used, they may have to be measured with some frequency. So, there's all this control from the outside world. And if we get into more complications, qubits are noisy. They don't fix themselves But there's a cure for that in the form of something called quantum error correction, where qubits are organized into ensembles that encode the states that you want to represent. And that also lend themselves to conducting or interacting, conducting gates, interacting with other logical qubits, carry out the logical gates that are represented in the computation or in the algorithm. That's all possible. Part of quantum error correction code means that the qubit ensemble has to, at some frequency, at points in time, it has to present to the classical computer side a map, kind of a spatial temporal map of where it's, of what its measurements are reporting about errors. It's kind of an encoding of where the errors are. And so, on the classical compute side, it has to receive this map and it has to deduce from it exactly which qubits are in error and then go tell the control circuit to insert a gate or correction to go fix the errant qubit or one or more qubits. So, there's a lot going on to preserve what we could just loosely call the coherence of that system so that it lasts for the duration of the computation. Dimitrios Donavos: So, I'm imagining that with a classical computer, I can go down to my local electronics store and buy one and bring it home and set it up on my desk. I doubt the way you're describing quantum computing you can do the same with a quantum computer. So, can you just describe a little bit about what a quantum computer looks like and what environment it typically runs in? Michael Di Rosa: So, because this involves quantum mechanical states that are invested in physical devices preserving quantum behavior in all its coherence, you can imagine that these are special devices and they live in special environments. So, depending on the technology that's used, and again, qubits are physical things, just like transistors are physical things holding our binary logic, depending on the technology, they'll need to be kept at, put it mildly, very cold temperatures close to absolute zero. And then often they need to be kept, again, depending on the technology, in near perfect vacuum. So, these are not ordinary states. There's nothing you're going to put on your pocket or fold and take with you as you go walk around and have a conversation. So, they are very particular about the environment they need to be kept in, and that all is related to maintaining quantum coherence for as long as possible. Dimitrios Donavos: So, one of the ways as a non-expert and somebody who's trained as a cognitive neuroscientist that I try and think about the difference between quantum more traditional computing is that quantum computers by their very nature handle uncertainty better than traditional computers do. That is to say that they are able to process information that traditional computers simply can't. And it sort of changes the scope of the problem for what a computer that is a quantum computer can tackle versus a traditional computer. What are some of the differences in terms of the types of problems that people can try and solve with a quantum computer Michael Di Rosa: You know, we're, we tend to think of, for these, it's often been said in these introductions is that, you know, a classical bit is zero or one and a quantum bit is both at the same time. Instead of thinking of it that way, again, maybe this is sort of just remove some of the gloss if that's possible of quantum computing. A qubit is every bit as precise, if a, as a classical bit, if a classical bit is being in either New York or Los Angeles, but nothing in between. A quantum bit could be in Omaha, Nebraska. Every bit is precisely as being in New York or Los Angeles. It's just that for us back in the human world, when we ask of it, finally, in some final disposition, we ask if it's either in New York or Los Angeles. And then at that point, the quantum system will project itself into either. But before we ask that question of it, it's precisely where we put it. So, and this gets in the aspect of that quantum systems are delicate and they decohere and all this. So, they have their own difficulties of maintaining this precision. But again, the state of a, and it is a state for a quantum bit is every bit as precise as, again, theoretically, as what a classical bit would be, within its limitations of being zero or one So, the, you know, the types of algorithms you can perhaps do with quantum, they take advantage of, let's say this extra dimensionality that qubits present, that quantum algorithms present. And, you know, again, by the, you know, more conventional picture of how, or conventional history of how quantum computing developed, you know, was Feynman who and others who perhaps proposed that, if we want to calculate quantum mechanical systems, why don't we use quantum mechanical objects to do the computation? And so, they're quite efficient at describing the dimensional space necessary of a quantum system. And they can be put toward the gates and interactions necessary to kind of simulate quantum systems. So often they pose problems too large for a classical system to go simulate, but a quantum problem can be represented compactly within quantum objects and then they're put forward for quantum computation. Dimitrios Donavos: So, when I think about quantum and I think about what makes quantum special, I think about the concepts of superposition and entanglement, which I think you've gotten a little bit into in your description there. In entanglement, if you flip two coins, they are independent of each other. The flipping in one has no bearing on the flipping of the other. But in entanglement, the qubits are linked and they influence each other. Can you unpack that a little bit for our audience and help us understand the significance of that and what that means in terms of what quantum computers can do as a function of that? Michael Di Rosa: Yeah, for at least for quantum computation, what that really gets to is that there are these special correlations between two quantum objects. In this instance, the information in those two-quantum object is bound within those two objects. If you ask one of those two objects, which state it's in, like you said, if you just get a coin flip, you would just get, you know, just random information and if you were ignorant of that result and you go ask the other, you would again get, you know, an answer that was, you know, kind of random between two states, these so-called computational basis. But entanglement is making use of that special correlation between those two objects. So, I wouldn't necessarily look at it as, you know, this spooky action at a distance, again, as it's sometimes cast as, but that there is an opportunity to take advantage of these special correlations called entanglement. So yeah, it is, I think, true that really some of the unique aspects in information processing and quantum computing does come by superposition and also entanglement. And the most successful algorithms will take advantage of those two. Dimitrios Donavos: So, to frame it in a way that a non-expert might appreciate, I think about, you know, how a classical computer and a quantum computer might attempt a similar problem and have different sort of superpowers. So if we think about traversing a maze, a computer might traverse that maze, a traditional computer, by literally going through every single possible route through that maze, where a quantum computer could actually do it all at once in parallel. Is that an appropriate way to think about how a quantum and classical computer might tackle that problem differently? Michael Di Rosa: Remember back to this, you know, when we talked about, you know, qubit having a precise value, anywhere between New York and LA. But when you ask it, you just get one answer. Am I in New York or in LA? After the algorithm runs and you ask a quantum computer an answer, it's just going to give you an answer. So, the, the analogy to think about for, let's say, solving this particular maze problem, as it were, the algorithm would have to be set up more like, you know, drawing on my you know, and what others do as well, drawing on like a spectroscopy analogy or an interferometer analogy. You construct your algorithm so that the right paths, if or maybe there's only one, they lead to some kind of constructive interference. So, you get like a sharp peak in the answer when you finally read it out. The ones that dead end spiral into the middle, whatever, they destructively interfere. And so any answer, any peak that those types of answers or solutions kind of get suppressed. So that by the time you run this, and again, everything is in the algorithm, if everything runs well, the answer you get, the peak that you get will be at the solution you're after. So think of it in that way as a big interferometer, if that helps. Dimitrios Donavos: That's a good analogy. So, if we think about superposition and entanglement as sort of the superpowers of quantum computers, what would be the kryptonite? Michael Di Rosa: The world. [Laughter] Dimitrios Donavos: You're gonna have to unpack that a little bit. Michael Di Rosa: The world. So yeah, I mean, you know, so it is, you know. Dimitrios Donavos: The world is a noisy place. Michael Di Rosa: It is a noisy place and so it's almost conspiratorial, mean there's like, there's this all this allure of computing, of quantum information processing through the fundamentals of quantum mechanics. yet, but these systems, they are also very sensitive to things of the outside world. And when I say the outside world, it is if you, you know, if you look at whatever is proposed as the quantum mechanical object that, you know, as the qubit, it's everything outside of it that is the world. So, you can't live in isolation. We need to control it. We need to ask it. We need to measure whatever the answer is. We need to set gates and everything else. So, we become the outside world. So almost invariably qubits are are going to decohere and so this is quite unlike again our classical bits where, I don't know, if you had a transistor and you, and I don't know, you had one of those cans of air and you gave it a puff of air on it or you waved it around or you carry your laptop on an airplane, it's perfectly fine. I don't think you'll be doing that necessarily with, with a quantum computer. They have to be very well, very well protected. But then, but even then, because we intrude on what is potentially a perfect environment with to measure, to control, set gates and everything else. Then, you know, these, the systems are going to lose all those properties of coherence, superposition, you know, the coherence of entanglement and all that other stuff you know, quite quickly. so then, but there's hope. You know, there's hope. There's actually, there's a few items in the list. mean, quantum mechanical objects, I know we kind of paint them as frail, fragile objects, but really when you look at like the energy, like the sort of the energy scales of, of, of some qubits, it's like, well, that's not that bad. I mean, you know, you know, for some for some qubits, you might need something the equivalent of, you know, like some bright light shining on it. Again, absent everything else, like, okay, that's not too bad. Unfortunately, it's also, you know, there's other forms of noise that might mess it up. It energetically doesn't look so bad. And then secondly, there is fortunately a form, know, forms of error correction that if errors, again, they, they, you know, invariably occur, but if they occur at a low enough rate and we can aggregate these qubits in particular ensembles that act like little machines to go detect errors, announce where the errors are, tell us where they are. And then we sort of, you know, puff in the correction. All this might hold together. So, the, so the allure of quantum computing comes back, you know, quantum computing, you know, first, theoretically, it's like, great. These, there are some powerful algorithms, but it's never going to work. Qubits are fragile. But then it was revived with a lot of hope to say that's true, but there's quantum error correction and there's other aspects that go along with that. So all that's to say is that there is certainly, if not yet a technical path, certainly a theoretical path by which this can work. [Music] Outro: Thank you for joining us. For more information about IARPA and to listen to part two of this two-part series, visit us at I-A-R-P-A.gov. You can also join the conversation by following us on LinkedIn and on X, formerly Twitter, at IARPA News.. |

[00:00:00]

Bluvstein, D., Evered, S.J., Geim, A.A. et al. Logical quantum processor based on reconfigurable atom arrays. Nature 626, 58–65 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06927-3

Gambetta, J.M., Chow, J.M. & Steffen, M. Building logical qubits in a superconducting quantum computing system. npj Quantum Inf 3, 2 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-016-0004-0

Ristè, D., da Silva, M.P., Ryan, C.A. et al. Demonstration of quantum advantage in machine learning. npj Quantum Inf 3, 16 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-017-0017-3

Zhu, D., Cian, Z.P., Noel, C. et al. Cross-platform comparison of arbitrary quantum states. Nat Commun 13, 6620 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-34279-5

The demand to solve increasingly complex problems is accelerating beyond the capabilities of traditional computing approaches. Quantum computing promises to revolutionize a host of industries by enabling rapid solutions to complex problems that are currently intractable for more traditional – or classical – computers.

As a primary funder of quantum research since 2009, IARPA-sponsored efforts have resulted in multiple world-record demonstrations of quantum computing capabilities, including achieving a “Quantum Advantage” – when a quantum computer can solve a problem more efficiently than a classical one. IARPA-funded quantum efforts have also led to over a thousand publications, dozens of patents, and the 2012 Nobel Prize in Physics.

In part two of this two-part episode, we discuss with Michael why quantum is such an "IARPA hard" problem, unpack IARPA’s history of quantum breakthroughs over the last decade, explore what applications might come from quantum computing in the future, and much more – including how Michael’s first foray into engineering and maybe even the world of quantum might of have had its roots in the mechanics of bowling alley pin setters.

| Timestamp | Caption |

|---|---|

|

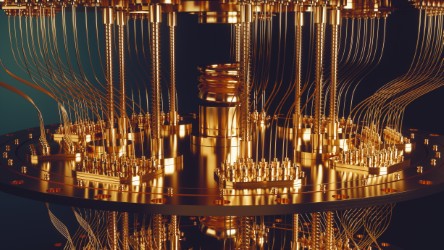

[Music] Intro: IARPA sponsors research that tackles the intelligence community's most difficult challenges and pushes the boundaries of science. We start with ideas that often seem impossible and work to transform them from a state of disbelief to a state of just enough healthy skepticism or doubt that by bringing together the best and brightest minds, we can redefine what's possible. This podcast will explore the history and accomplishments of IARPA through the lens of some of its most impactful programs and the thought leaders behind them. This is IARPA, Disbelief to Doubt. Dimitrios Donavos: Welcome back to IARPA, Disbelief to Doubt. I'm your host, Dimitrios Donavos. In part two of this two-part episode, we continue our conversation with former program manager, Dr. Michael DiRosa. If you’re just joining us, make sure to go to iarpa.gov forward slash podcast to listen to part one of this episode where we cover some of the basics of quantum computing. In part two, we discuss with Michael why quantum is such an IARPA hard problem, unpack IARPA’s history of quantum breakthroughs over the last decade, explore what applications might come from quantum computing in the future, and much more – including how Michael’s first foray into engineering and maybe even the world of quantum might of have had its roots in the mechanics of bowling alley pin setters. Take a listen. Dimitrios Donavos: So, I think you've hinted at this as you've walked us through quantum computing, but I wanted to ask you in your own words, what makes quantum such an IARPA-hard problem? Michael Di Rosa: This aspect for computing, for quantum information processing, it's a multidisciplinary endeavor. And if you want to make progress on it, in particular over this horizon, or at least a glimpse at it, of what does, to use a longer word or phrase, universal fault tolerant quantum computing look like, that figures in all the aspects of quantum error correction and conducting logic operations in a way that best preserves quantum coherence, keeps errors and faults from propagating. To do that, through that model, through that paradigm for quantum computing, draws on, well, you name it, physicists, material scientists, engineers, computer scientists, theoreticians’ mathematicians, all toward those kinds of objectives. And they all need to be talking to one another because you can imagine that the theorist that comes up with the architectural paper needs to talk with the experimentalist to see if that's feasible. The experimentalists need to discuss what types of errors the real physical system has so that the theorists, who in this case don't mind getting their hands dirty working with experimentalists in real numbers, they might be able to arrange an architecture that is less vulnerable to the types of real noise that is present in these physical systems. So, it really is by that symbiosis that you can make progress in this particular field. And IARPA has a long history of having the types of programs where people from various backgrounds can join together on a team and make progress. And in that regard of...IARPA is a place right to make progress in a field like quantum computing. Dimitrios Donavos: So, you've mentioned error corrected and fault tolerant quantum computing. Can you just step us through what exactly that means and why it is so important in terms of the focus of IARPA research in the quantum domain? Michael Di Rosa: So, keeping in mind that this is the likely future for quantum computing, this mouthful of universal, full tolerant quantum computing. What that means is that the logic operations we normally think of as a programmer, I'm going to devise an algorithm and at some level of assembly language, I can distill it down to a handful of gates, not gates, controlled not gates and things like that. When I make those requests for logical gates through an algorithm. They'll be sent not to, they'll be acting on, I should say, more collectively, more holistically on the set of qubits encoded into a quantum error correction code called a logical qubit. And just that command of a gate will set in motion all these coordinated actions and choreography on the individual physical qubits that are composing the logical qubit, but to the programmer, what I understand to be my logical, my, my computation is taking place on these now abstract blocks called logical qubits. Underneath it, there's a lot of machinery sending commands to the physical qubits that compose a logical qubit, but to the program at some level, all I know is that I made a command on a logical qubit to carry out a gate either with it, you know, on, on itself or perhaps on a neighboring logical qubit. Michael Di Rosa: So that's where the kind of quantum error correction comes in. Quantum error correction will keep, will preserve that quantum information within that block of a quantum error correction code. The aspect of fault tolerance comes in, well, because, you know, keeping logical qubits, you know, having them preserve logical information isn't enough. That's just memory. I need to compute, I need them to interact. So an easy way to do that possibly would be, if your time I want to gate with another logical qubit, I'm just going to unpack or unfold my logical qubit and have it interact in a simple way with the other logical qubit. And after that interaction, I'm going to fold them back up into their quantum error correction codes and proceed. However, when you do that, you introduce the possibility of spreading errors, you know, too quickly, too quickly for your quantum error correction code to compensate. They can spread exponentially or geometrically, you know, one to two to four and so forth. So, the way that you can better preserve that quantum information and not build up errors to the failure of your quantum error correction code is interact logical qubits while keeping them in their quantum error correction codes. And that's not often easy. It does add a complication. It can be done. And, but that is also a necessary ingredient for maintaining, you know, this model for quantum computing. Have quantum error correction codes to clean up errors when they occur and also abide by say a policy or a rule of fault tolerance where I keep quantum information within those quantum error correction codes, don't unpack them so that they're preserved. And there's other aspects of fault tolerance that are a little more nuanced. But for the most part, you have to conduct all the algorithms such that errors don't spread in some uncontrollable way. That's just the machinery of quantum computation that's to say nothing of course, you know, of the algorithms that are needed for gaining the computational efficiencies that quantum computation promises. Dimitrios Donavos: The algorithms that are needed in order to derive these efficiencies are those things that are happening in the classical world that get applied into the quantum world? Or am I not thinking of that correctly? Michael Di Rosa: This is a fascinating question. So, algorithms are what make computations effective. We use them all the time in our daily life with regular computers. So, quantum computers are not faster computers. I don't believe there's proof of some general superiority of quantum computers. To make quantum computers effective, you need to come up with clever algorithms that take advantage of this paradigm for computing. And again, in theory, and by the example I gave earlier, it can be effective. For say, physics problems or chemistry problems, to use those examples, computations there. that are intractable presently could be done far more effectively and quickly and such by instituting or finding, developing an algorithm that works with quantum computing. So that's the other hard part too, is learning how to work with quantum computing define effective algorithms and exactly why quantum computers provide in those particular instances the advantages they do. That's also a topic of debate. Some might point to superposition, some might point to this uniquely, quintessentially quantum mechanical resource of entanglement, and there are other reasons. But nonetheless, just to boil it down to maybe a simple definition of effectiveness. If an algorithm is effective on a quantum computer, it will reduce the number of steps you would take to get some desired result to something substantially less than what it would take on a classical computer. Dimitrios Donavos: And you mentioned error correction, which is important from the perspective of how IARPA has approached quantum computing and putting an emphasis on the need for error correction. And that leads us into the topic of just talking about IARPA in terms of being at the forefront of quantum research since 2009, when we launched the Coherent Superconductive Cubits program. Work funded by IARPA was named Science Magazine's Breakthrough of the Year in 2010. And I'm wondering if at a very high level, you can just walk us through some of the technological accomplishments that we've had in that area across our portfolio since that time? Michael Di Rosa: Over that span from CSQ, to give it a shorter name, IA RPA has from the outset, has constructed programs that try to define, that always auger toward universal fault tolerant quantum computing. So, when CSQ started, well certainly when we bring up things like error correction codes, we know we're going to need more than one qubit. We're going to need, you know, several qubits, maybe a dozen qubits or more, and they all have to perform well. So, when CSQ was formed, there was already the recognition that yes, we need to make good qubits, but we need to make them better than what was available at the time and also make them in a way that lends itself to scalability and even reproducibility. So, the way the programs are built is yes, but yes, quantum computing, but do it this way. Michael Di Rosa: Again, so it sort of begins to define and push that path for this universal fault tolerant quantum computing. I think the next program after that was MQCO or multi qubit coherent operations. So now we're going to throw in the C. Coherent. So great with CSQ, we've made some numbers of qubits. It happened to be for superconducting style of qubits. So yes, but now we're going to explore a variety of platforms. And after you make your platform of qubits, do something representative of a circuit with it, because we want to look for how the real world intervenes, invades, like through crosstalk and things like this. So do something in a mini algorithm that involves all the qubits you've meticulously fabricated or arranged So again, it takes another step, another, you know, keeps chipping away at this, at the obstacles, at this path for universal fault tolerant quantum computing. I should add that under CSQ, mean, a lot of this, it's this interplay of theory and technology as well. So, you also need technology and device physics to give this, give this inspection to, you know, to get up to the horizon and look beyond it. So, there were some technological devices that were quite enabling that were built under CSQ So, it begins to build kind of the community in the ecosystem and kind of like the overall technical apparatus, you know, on several technical platforms to proceed in this direction. Think there was another program called QCS quantum computing systems. And that was a look at, actually it was a lot of software development in QCS that asked the question of if you wanted to, let's say, you know, run a particular problem or an algorithm how well does your quantum processor have to perform? So, it's taking a look at, yes, you want to do something with your processor, but look at it from some fundamental perspective, modeling and software. What are your targets for the performance your devices have to be at? How many do you need? Things like that. So, I think that that set the stage for a more sort of computer science, you know, look at quantum computing. There was a lot of intensive work, you know, represented by CSQ and MQCO on developing the device physics. But we also needed to know what metrics and benchmarks, you know, they would need to hit. And then after that came LogiQ, which said, great, technically we have the foundations now, enough qubits that we can think plausibly about running a very particular algorithm on them called quantum error correction. So, and that began in, I believe 2016. And at that time, I don't believe that there was error corrected logical qubit at the start And by the end of that program, roughly seven years later came for all the research teams, the four research teams, instances of error corrected logical qubits. So that was a prime instance of really putting theory into demonstrable practice. This worked. And I'd say over the string of programs, they continued to show that fundamentally as best we can peer down this path, you know, with the noise that we have and the apparatus we have, there's no real fundamental obstacle to quantum computing. Things are behaving again as best as we can inspect it, as we expect it to. So that all set the stage for now quantum information processing or the fundamental steps for that with quantum error correction codes or logical qubits. Dimitrios Donavos: You've discussed our long history at IARPA in terms of quantum research, but I want to delve into what has motivated you to launch the ELQ program and what you hope to accomplish with that effort? Michael Di Rosa: When I came to IARPA, it was to run the latter part of the program called LogiQ, which began with the objective of proving that these quantum error correction codes indeed could work and that fault tolerance also works. So, this was by a variety of technologies, putting theory, putting theory into practice. And by the same token, when theory and practice experimentalists get together, often something new arises. And I think by the end of logic, there was a much greater understanding of what quantum error correction means and not just how to demonstrate it in physical systems, but how to go about quantum error correction, perhaps more efficiently, how to study it, how to characterize it. And so that was a success by the end of the program, but quantum information processing itself needs more. It needs logical qubits to interact and the complexity of that problem going from single logical qubits to two or more that interact to do something useful in the context of quantum information processing, you know, the next great leap, the next great objective for the field. So that was the inspiration behind starting ELQ or entangled logical qubits is to define a program that set that particular destination, set boundaries, set boundaries for that journey for maintaining fault tolerance and various other aspects that maintained relevance for the field of universal fault tolerant quantum computing, and by the program's end, show demonstrably an outcome for entangling logical qubits, again, this quintessential resource now done between logical qubits, not just physical qubits, and do so a way that we can report something we can measure, like the success in this case of using entanglement for teleportation, which turns out also to be necessary for quantum computation. So overall, that was the goal for ELQ. Take the next great step beyond logic in using and developing logical qubits to the next sort of the next horizon for universal full-tolerant quantum computing. Entangling them, doing something demonstrably useful for quantum information processing for quantum computing, and do so with, by building an awareness for what the challenges beyond that will be. So, it's not an objective for itself. It's done in such a way that allows us, IARPA, the community in general, to know what the next challenges are ahead. Dimitrios Donavos: What are we striving to achieve, thinking about the big picture with our quantum research at IARPA? And why is it important from a science perspective? Michael Di Rosa: From an IARPA, and also from a science perspective, I think we're all trying to get our best view, our best sense of what this future is for computing. It's a model for computing and architecture that sits far apart from classical computing. We talked about some of the synergies about the care and feeding with classical computing, but in terms of how to handle quantum computing, how to think about it, how to, well, and also on the technology side, you we also need to learn what are the limitations, I would say, or of the technologies themselves. So, we need to know their limitations, what noise mechanisms they present, what noise mechanisms might be damaging, how they might be countered, in what ways with quantum error correction, how to predict the behavior of physical systems. So, there's a healthy interplay necessary when we try to glimpse this future of again, trying to implement a theory, put that into practice, but also knowing that the limitations of the technical expressions have to be fed back into the theory so that we could find a way that might either overcome these limitations or give experimentalist focus on what noise sources they need to combat. Dimitrios Donavos: Tackling this very difficult IARPA hard problem requires this multidisciplinary, multi-team and worldwide effort that you've talked about. IARPA in its history has played a significant role in investing in quantum research and helping build out these communities that didn't necessarily exist. I want you to just think about what you think the legacy is going to be for IARPA's involvement in quantum? Michael Di Rosa: That Legacy? Well, there's a longer story to this preceding IARPA, there was ARDA, the Advanced Research and Development Activity. And part of their charter, and this began in, I believe in the mid 1990s, late 1990s, and among their charter was to investigate the potential of quantum computing. So, they had programs in quantum computing. ARDA became the Disruptive Technology Office. And in 2007, when IARPA was stood up, DTO was absorbed into IARPA. So, in a sense, there was already a legacy of, of looking ahead to the future of quantum computing prior to IARPA. And that was continued through IARPA. So, to pick up with IARPA, they continued this particular pursuit, looking at universal fault tolerant quantum computing, building the technologies in cooperation with also the computer science and the theory necessary to work cooperatively with the experiments. So, I think the legacy for IARPA will be this this decided focus on the harder problem for the future for quantum computing. That the future needs to involve all the elements of theory and experiments now working side by side. And I think that has laid the foundation for the field and will continue to. Dimitrios Donavos: Looking over the horizon, what kinds of applications from quantum computing do you hope to see in the next 10, 20 years? Michael Di Rosa: One of the things I think quantum computing in the nearer term can do is aligned with those initial visionary ideas for quantum computing that would simulate physical systems and physics systems. It might be possible to answer, say, meaningful questions about physical systems through quantum computers. Does it behave in this way, which the outcome expected for this ensemble to get useful information and insights about physical systems that would be too tedious or laborious to do through experiment. So that, I think, is one of the things we could look forward to in the next decade or so, this aspect of simulating physical systems. Dimitrios Donavos: And what are some of the applications that we might get from that simulation of systems? You talked a little bit earlier about chemistry and biology, and I'm curious if you could just expand on that so that our audience might understand what the potential is for quantum. Michael Di Rosa: Depending on the, let's say for chemistry, often it's helpful to know what the, well this gets into some specifics about chemistry, but sometimes it helps for a complicated molecule to know exactly what its ground state energy is. It might help in areas of drug discovery with the folding behavior of a protein is. And to do so without, say, you know, all the types of trials that experiments would involve, that it might reduce the time it takes to come up with a particular solution that's workable, so that through quantum computing, you might be able to do some of the groundwork you would otherwise have to do with experiments. Dimitrios Donavos: I want to put you in the position of being an adolescent reading a scientific novel that talks about this promise of quantum computing. And I want you to just imagine, if you were thinking of it from this perspective, this wide-eyed perspective, what would be a really impressive application of quantum sometime in the future that we might be talking about 40, 50 years from now? Michael Di Rosa: At the very least, it'd be neat if this became maybe more than 50 years, but it became what we consider today to be just a regular calculator. Now, it doesn't mean you're just going to do simple arithmetic and everything else, but you know, let's say my homework problem is to go calculate a rather complicated response. It could be, again, in physics, it could be in any particular problem, it could be, I don't know, financial markets, whatever it might be And, it would become at that point, because we've been sort of accultured to think about things algorithmically, problems algorithmically, and how to take advantage of quantum information processing to solve that more efficiently, that I'd be able to set up the problem, and maybe that’s even, that comes rather intuitively, and get the answer that I would expect, or not that I would expect, but get the answer as simply as just pushing buttons on a calculator That would be fantastic. And leading up to that point again, is not just the technical underpinnings that makes a quantum computer possible wholesale shift in how we think about things algorithmically problems algorithmically and to take advantage of this so that we could approach this much like I'd say a top computer scientist approaches databases or, you know, particular problems today, not needing to know a lick of the physics that goes on within the machines that are doing the processing. But certainly, a very skilled approach in how to be resourceful at putting together the algorithms that accomplish particular objectives. So that's a tall order for 40 to 50 years from now, but I would hope that's where we're headed. Dimitrios Donavos: So Michael, I want to give you the opportunity from a topic or scientific perspective to address any topics that we didn't cover today. Michael Di Rosa: You've been quite thorough. I would just add the, perhaps the understatement that quantum computing is hard, but it's precisely that because not only is it hard, but it does seem as best we know to be sort of the, you know, the ultimate means for information processing. And it has some, it's too tantalizing to ignore. So as tantalizing as it is, it's also very hard. But I think that that's why it's been an extremely exciting arena for research. Dimitrios Donavos: And fits right into IARPA's portfolio since hard is pretty much where we start think about funding IARPA programs. I want to close by just talking a little bit more about you personally, and I'd like you to just tell our audience something about you they might be surprised to learn? Michael Di Rosa: Well, maybe, maybe it wouldn't be too surprising. Would you believe I was a bowling alley mechanic, employed bowling alley mechanic? Dimitrios Donavos: Wow. No, I would not. Although with mechanical engineering in your sights, I guess it doesn't surprise me all that much. That sounds like a dangerous occupation. [laughter] Michael Di Rosa: It definitely was back behind the machines. Those could do some brutal things to you, any appendages, but it was a good learning ground as well for learning how things work and often why. Actually, one cool thing about that, it had its own form of information processing. It had really a mechanical computer in the back, and I was always fascinated to learn about that. Dimitrios Donavos: I presume that when you were back there making any adjustments that you weren't under the threat of a bowling ball racing down the hardwood? Michael Di Rosa: I wasn't going to give anybody an easy target, no. Dimitrios Donavos: Okay. [laugher] Dimitrios Donavos: Describe a little bit what this mechanical computer looks like because now you've piqued my curiosity? Michael Di Rosa: I'd say let's call it a gearbox, the size of a small automotive transmission. But back there were gears, levers, eccentrics, cams that would make the decision after you threw a ball. Of course, if you get a strike, what does it do? It sweeps away the pins and gives you a fresh set of 10. If you didn't get a strike, it would sweep away the pins and reset it, which you had left. And so that decision took place all mechanically. There were scissors that grabbed pins. If there were any, if they fully closed, if all of them closed, it made one decision. If one or more were open, it made another decision and spent a lot of time evaluating those, building them, rebuilding them. It was kind of fascinating what it could do. I mean, certainly machines afterwards were replaced by, by electronics, but there was a time, these were old pin setters, know, dating from the fifties when this was the most robust way to do it. Dimitrios Donavos: Would it be a stretch to say that those were rudimentary gates that were opening and closing and that this was your first foray into quantum mechanics? Michael Di Rosa: Indeed, it was. Dimitrios Donavos: And Michael, what do you do for fun when you're not trying to solve some of the hardest problems in both the open scientific community and the IC? Michael Di Rosa: Well, as immersed as I am in technology, I also enjoy being thoroughly unplugged. So, whether that's, you know, time in the West, you know, time away somewhere, usually where cell signals don't reach. Dimitrios Donavos: I think all of us can appreciate that, especially in an era where we are overwhelmed with noise that comes from all of the interconnectivity that we have at our disposal. Michael, I want to thank you. This was a really enlightening and engaging conversation. I appreciate your time and insights today and look forward to hearing more as ELQ unfolds over the next several years. Michael Di Rosa: Dimitrios, thank you. Absolute pleasure. [Music] Outro: Thank you for joining us. For more information about IARPA, and this podcast series, visit us at I-A-R-P-A.gov where you’ll find resources and citations for this and all of our episodes, including examples of quantum computing systems. You can also join the conversation by following us on LinkedIn and on X, formerly Twitter, at IARPA News. |

[00:00:00]

Bluvstein, D., Evered, S.J., Geim, A.A. et al. Logical quantum processor based on reconfigurable atom arrays. Nature 626, 58–65 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06927-3

Gambetta, J.M., Chow, J.M. & Steffen, M. Building logical qubits in a superconducting quantum computing system. npj Quantum Inf 3, 2 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-016-0004-0

Ristè, D., da Silva, M.P., Ryan, C.A. et al. Demonstration of quantum advantage in machine learning. npj Quantum Inf 3, 16 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-017-0017-3

Zhu, D., Cian, Z.P., Noel, C. et al. Cross-platform comparison of arbitrary quantum states. Nat Commun 13, 6620 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-34279-5

Enjoy this sneak peak of IARPA: Disbelief to Doubt Episode 4! In this upcoming episode of Disbelief to Doubt we speak with former Program Manager Michael Di Rosa and explore how quantum computing differs from classical computing approaches, how this technology may eventually change the world, and how IARPA has been at the forefront of quantum research for nearly two decades.

| Timestamp | Caption |

|---|---|

| Michael DiRosa: That to do this with a quantum computer would take, about some tens of millions of qubits. And the algorithm itself would take some tens of billions of steps. after that, through this algorithm with a quantum computer, you would arrive at an answer to that problem. That if left to a classical computer would take, round estimate, a quadrillion years to solve. That's a long time! Longer than the age of the universe. There is the allure then for quantum computing to be applied to other problems and to the earliest visionary ideas for using quantum computers and that was for simulating physical systems, for simulating physics and related problems in chemistry, biology, medicine. How could we arrive at superconductivity at room temperature? How could we discover drugs and cures faster than we do now? So, there's this sense that quantum computing is not superior in every regard to classical computing. But there are some classes of problems that gives it impetus to discover what this frontier of computing might be like. |

[00:00:00]

IARPA invests in high-risk, high-payoff research with the goal of providing our nation with an overwhelming intelligence advantage. Developing scientific breakthroughs that challenge the state of the art requires IARPA Program Managers (PMs) to take ideas from a place of “disbelief to doubt” before successfully launching an IARPA program. As part of that development process, PMs must address a series of rigorous questions known as the “Heilmeier Questions” named after George Heilmeier, a pioneer in the research and development field.

In Part 1 of this 2 part episode, we sit down with former Office of Analysis Director Rob Rahmer to discuss his journey to IARPA, unpack the Heilmeier Questions and the role the play in IARPA research, and much more.

| Timestamp | Caption |

|---|---|

|